INTRODUCTION

For millennia, many civilizations thought that earth, air, fire, and water were the primary forces—the elements—of nature. Now, through new knowledge of how the world works, science has led us to realize that humanity itself has its own elemental power.

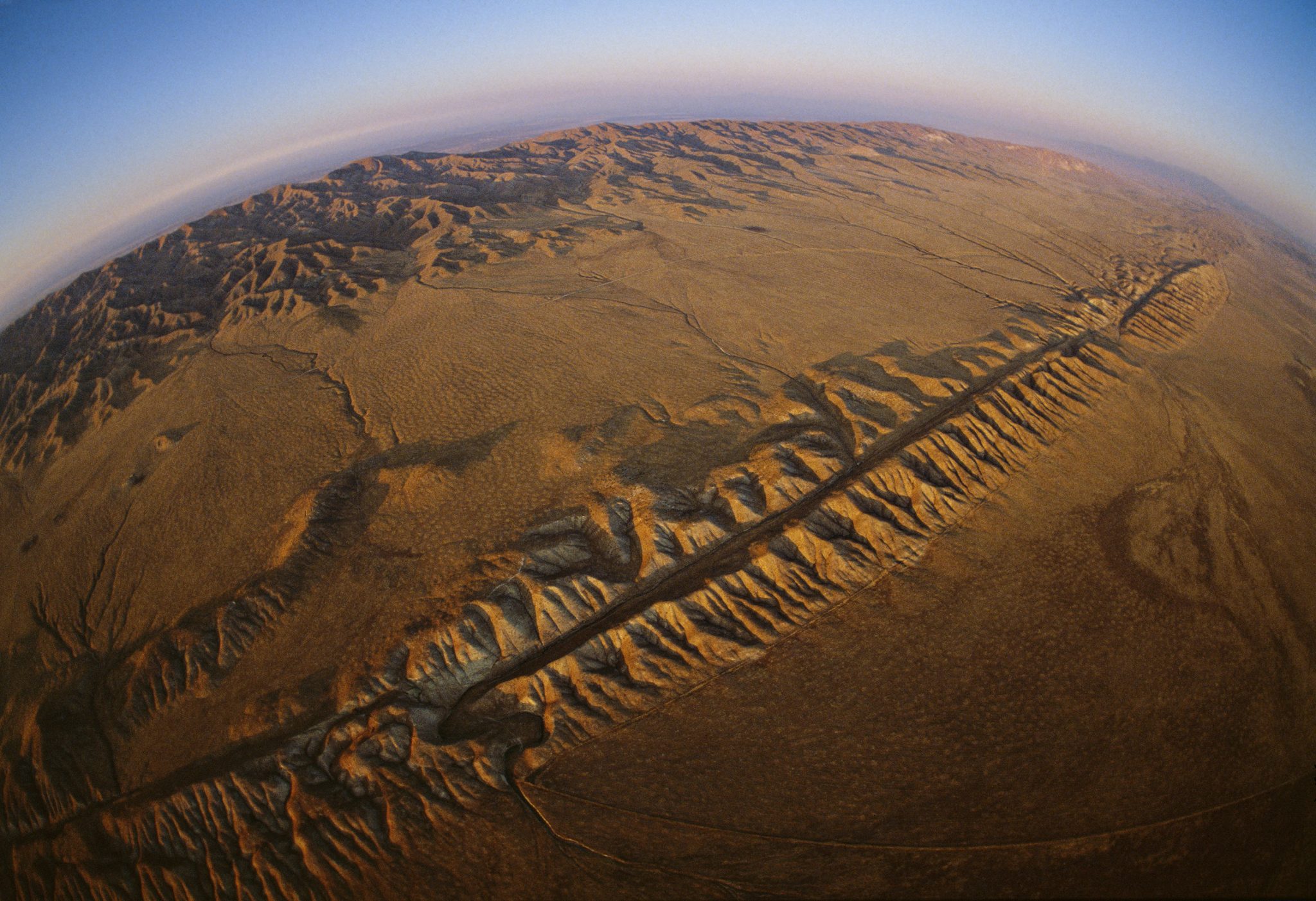

Earth scientists speak of natural tectonics. These are the forces cracking the planet’s crust with earthquakes and volcanoes. But humanity is a tectonic force, too. The combined power of our population, our technology, our survival needs, and our desire for affluence has reshaped the Earth as we know it.

James Balog—photographer, scientist, and filmmaker—recently dubbed the mechanisms of our impact “Human Tectonics.” In recognition of the widespread and long-lasting impact of humanity, the epoch of geologic time in which these impacts are taking place is known to science as the Anthropocene (pronounced “an’-throw-poe-scene”).

When the Anthropocene began is a matter of debate. Some scientists put it at 10,000 years ago, when agriculture became more prevalent than hunting and gathering. Many others peg it at 200 years ago, when the Industrial Revolution started spewing so much carbon dioxide and other gases into our air that the composition of our atmosphere changed. Still other scientists favor dating it to the first atomic bomb test: starting in 1945, the fallout from nuclear blasts laid down a worldwide layer of long-lived radioactivity on land and sea.

Human Tectonics produced the Anthropocene—and nearly everyone on Earth has benefited from the processes of the epoch. Increased industrial and agricultural capacity, improvements in water quality and medical care: these are big benefits to human life as a consequence of the Anthropocene. A dramatic increase in the human population during the past three centuries has resulted. The 20th century alone saw a fourfold increase in global population; as of 2018, there are 7.6 billion people on Earth. By the end of our current century, global population will likely reach 11 billion.

Ironically, that is both good news and bad news. Good news because people live at a generally higher level of health and comfort than our ancestors did. But it can also bring bad news for humanity and the environment around us.

Thus far, people have transformed more than 50 percent of the world’s land surface. 37 percent of all land area is now cultivated. Forests, deserts, and grasslands have been turned into farms and plantations, cities and suburbia. Populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians have plummeted 60 percent, on average, since 1970.

The Earth has warmed an average of 1.6 degrees F (1.0 degrees C) over the past 100 years. Some regions have seen two to three times that increase: the Arctic, for example, is warming four times as fast as the rest of the world. Storms, floods, and wildfires are more severe. Sea level is rising. Some of these impacts can be attributed to natural variation, but the science is crystal clear: most of these changes are a consequence of human impact.

The Anthropocene overturns centuries of Western philosophical tradition. It replaces the traditional idea that people are separate from nature with the realization that we are an integral part of it. As we reveal in our documentary film THE HUMAN ELEMENT, when people change the other elements, those elements in turn change us.

In THE HUMAN ELEMENT, Balog serves as our guide to the Anthropocene. The film takes us from Chesapeake Bay and the coal mines of Appalachia to the Rocky Mountains and the forests of California. We meet Americans on the front lines of climate change—and reveal what all this means for our children and our children’s children.