FIRE

On July 22, 2016, hikers in California’s Garrapata State Park reported a small wildfire burning in the forest— the result of an illegal campfire. By the next morning, the fire had grown to 2,000 acres, with officials issuing an evacuation advisory for the nearby community of Palo Colorado. The Soberanes Fire, as it would later be named, went on to burn more than 132,000 acres along the Big Sur coastline, with more than 5,000 personnel combatting the blaze at its peak. The fire was the most expensive firefighting operation in U.S. history to date, costing $260 million.

In 2017, California spent more than $700 million fighting fires, exceeding their budget by several hundred million and making 2017 the costliest year in California’s history. The Wine County Fires that burned through Napa Valley in the fall proved to be the most expensive in property damage, with nearly $12 billion in filed claims.

And, in August 2018, the Mendocino Complex Fire in northern California became the largest wildfire in the state’s history, burning more than 450,000 acres—300,000 of which were lost in the first two weeks. To cap the season off, the Camp Fire, a ferocious blaze that burned the equivalent of 10 Manhattan islands and destroyed 18,000 structures, claimed at least 88 lives in Butte County, just north of Sacremento.

The United States has a fire problem.

BIGGER FIRES

The American Northwest has witnessed a 1,000 percent increase in the frequency of large fires — 1,000 acres or larger — since the 1970s. In the western United States, the wildfire season has lengthened by 78 days, and the incidence of large wildfires in western forests is nearly four times what it was in the 1970s and early 1980s. The amount of land these fires burn is more than six times higher than it was four decades ago.

Climate change is the overarching condition transforming the landscapes of the American West. Scientists have found that 55 percent of increases in “fuel aridity” — the drier plants that feed fires — in western forests is due to climate change, contributing to an additional 10.4 million acres lost to forest fires between 1984 and 2015.

“We have changed our relationship to fire and that has rippled through everything: the atmosphere, the oceans, the biosphere,” says Arizona State University fire historian Dr. Stephen Pyne. “What we’re seeing now are the consequences.”

THE HUMAN ELEMENT

Perhaps nowhere is human-driven climate change more visually evident than in the fire cycle.

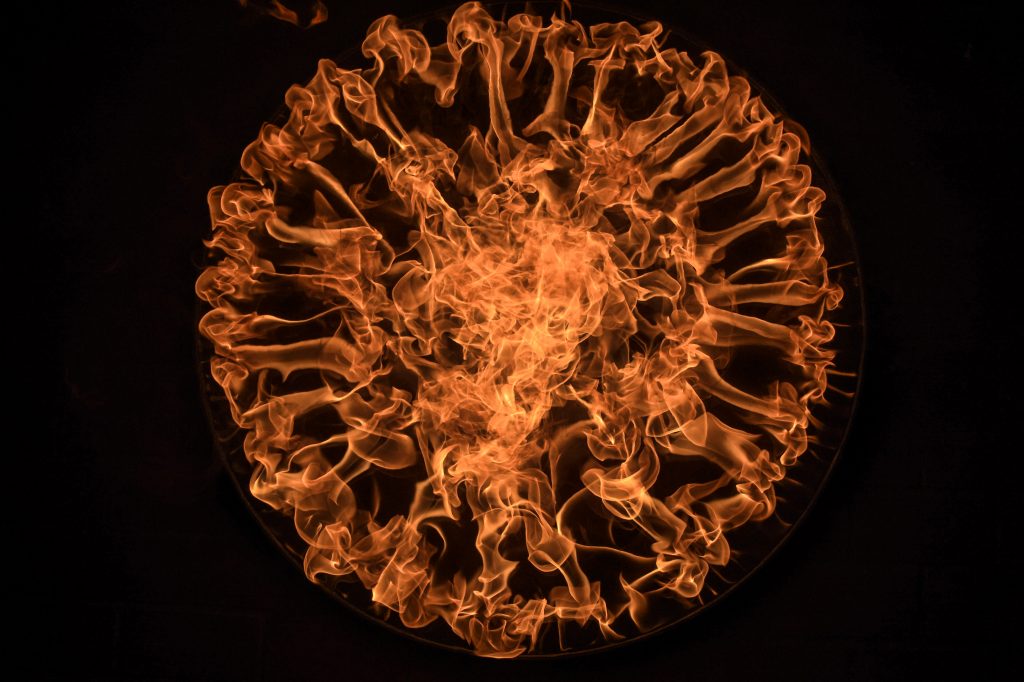

The original fire in our solar system is the burning star-ball of hydrogen and helium in the sky — the sun. On Earth, nature’s fires—nearly all of them caused by lightning bolts— have purified, transfigured, rejuvenated, recycled. The biological world thrives because of this natural fire.

But some three million years ago, hominids began learning how to handle natural fire. Fire was power. It radiated heat, light, and security. As our early ancestors progressed, so too did our relationship with fire.

In the 1800s, humans began to extract fossil fuels from our geologic past, breaking fire apart and putting it into machines, where we couldn’t see it. Contained in boxes, fire remained central to our lives, but it had been abstracted into what Dr. Pyne calls “industrial fire.”

We waged war against the natural fires, believing that they robbed us of timber, scenery, and living space. We suppressed them for decades. Then we moved into fire’s home: more than 44 million Americans now live in the wildland-urban interface—the area where homes and neighborhoods meet forests and dense expanses of shrubbery.

At the same time, hotter temperatures equal more fire. Human-caused climate change heats the air, then vegetation dries out, making it much more likely to burn. 2015, one of the three hottest years in the global record, was the worst year for U.S. wildfires on record. “We are organizing landscape in favor of big fires,” says Mark Finney, a physical scientist at the Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory.

Today’s wildfires are like nothing fire crews have ever seen before. The fires are bigger, hotter, more violent. The 2018 California wildfire season brought both the largest and deadliest fires in recorded history: the Mendocino Complex Fire and the Camp Fire, respectively.

“These big megafires have certainly changed the terms of engagement for the fire community,” says Stephen Pyne. “We’re beyond the age where can just throw firefighters into remote and hazardous settings under large fires and expect them to survive.”

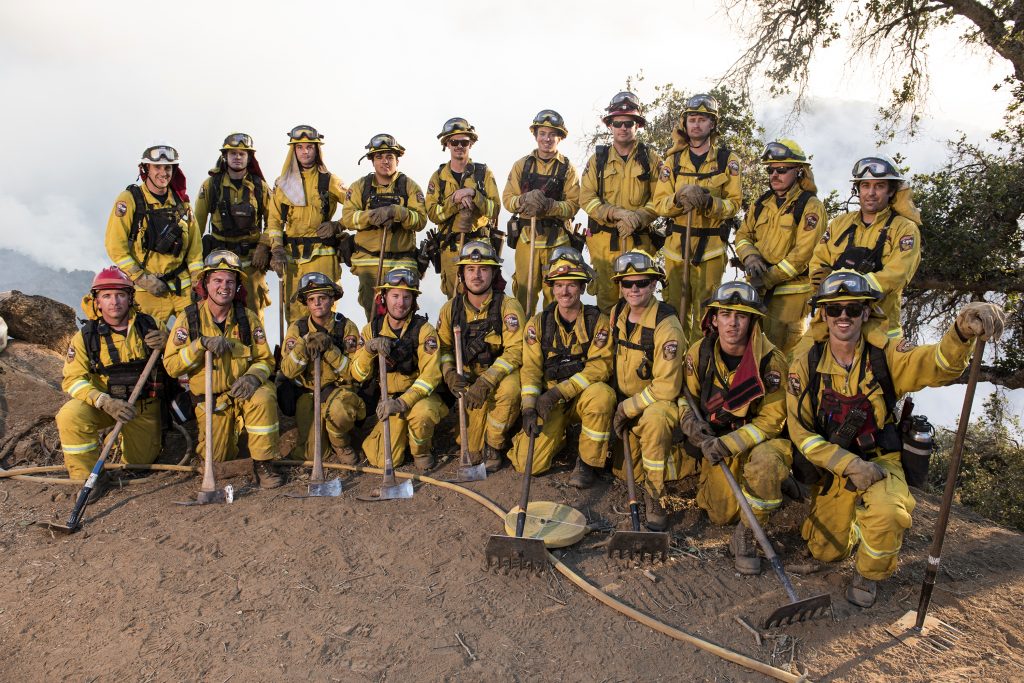

ON THE FRONT LINES OF FIRE

The air is thick with smoke and ash billowing ceaselessly from the Soberanes Fire. Yet Tony Howard, chief of the Mendocino Unit for Cal Fire, the California state firefighting agency, calmly smokes his Meerschaum tobacco pipe.

Howard has spent 26 years on the fire line, watching forests burn. “A long time ago, fire would just sweep through areas and nobody really fought the fire,” he says. “People would just burn around their houses and let the fire pass through as a natural progression.”

But things have changed. The destructive Soberanes Fire is evidence of that.

“It’s fire season pretty much year-round,” says Carignane Ferreira, one of the unit’s firefighters. “We’re burning way earlier, fire seasons go way longer.”

Ironies abound in firefighting. Today we are forced to fight fires with airplanes, helicopters, bulldozers, tanks, engines—all of which burn the same fuels that are heating the climate, drying out the forests, and making the landscape more flammable.

Every year, tens of thousands of men and women work to fight fires. In California and other states, some firefighters come from state prisons. When manpower is particularly stretched, firefighters from Australia and Canada pitch in too.

“It’s harder and takes more manpower, more resources to suppress fire,” says Bruce Miller, division supervisor with Cal Fire. In many cases, suppression isn’t even possible. Finney adds, “We have megafires now, and we have no control over them.”

LIVING IN THE “WUI”

Fires don’t only affect those deployed to fight them. They affect those who live in their habitat. The wildland-urban interface, or WUI, pronounced “who-ee,” is rapidly expanding in the contiguous United States. From 1990 to 2010, the number of homes built in the WUI grew from 30.8 million to 43.4 million. As Ken Pimlott, director of Cal Fire, says, “People are part of the equation now.”

In California alone, a third of homes are located in areas prone to wildfires. In an evacuee camp, Kris McKegney recalls the Soberanes Fire burning towards her home. “We were just throwing things in our car … trying to figure out should you take the expensive stuff or should you take the stuff you’re gonna need right now, like camping gear and pillows. And you can see it, the fire coming right down the hill getting closer and closer.”

McKegney was one of the lucky ones. She didn’t lose her home—or her life. No civilians were killed in the Soberanes Fire, thanks to the round-the-clock effort, and sacrifices, by Cal Fire. Tragically, Robert Reagan, a bulldozer operator on the Soberanes, was killed when his bulldozer overturned while he was cutting a fire line.

In 2017, more than 71,000 wildfires across the country burned nearly 10 million acres and destroyed 12,000 structures. Increasingly, homeowners in the wildland-urban interface are unable to find companies willing to insure their homes at a tolerable price.

Wildfires affect those living far away from the flames, too: 15,000 people die in the U.S. every year due to the effects of inhaling wildfire smoke. Scientists predict that by 2100, that number will more than double.

QUICK FACTS

- The annual number of large fires (>1,000 acres) in the United States has tripled since the 1970s.

- Wildfires burn six times more land area per year than they did four decades ago.

- The years of 2015, 2016 and 2017 marked the three hottest years in the global record.

- Arizona and California are the two states with the greatest projected increase in high wildfire potential days by 2050.

- The cost of fighting U.S. wildfires topped $2 billion in 2017.

- More than 44 million people live in the American wildland-urban interface.

- Every year, 15,000 deaths in the U.S. are tied to the respiratory stress of wildfire smoke.

RESOURCES

CalFire Incident Information: Soberanes Fire

The 10 most expensive wildfires in the West’s history

Costs to Fight 2017 California Wildfires Shatter Records

Insurance claims from California wildfires near $12 billion

InciWeb – Incident Information System

Mendocino Complex Fire now over 300,000 acres

Climate change has doubled Western U.S. forest fires

The wildland-urban interface in the United States

New analyses reveal WUI growth in the U.S.

One in three California homes prone to wildfires

California wildfires in 2017: A staggering toll of lost life and homes

Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity

Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes

Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests

U.S. WILDFIRE SMOKE DEATHS COULD DOUBLE BY 2100

Camp Fire Is 100 Percent Contained, California Officials Say